| « One hundred twenty one forms of falling ice: the new snow classification system | Rime falling from branches » |

What makes the thick curvy lines in frozen puddles?

My sister recently sent this photo of a frozen puddle, a little over a foot across. Something broke out a piece of ice in the upper right, but it’s mainly a complete glaze over the top. (The white dots are rimed snow crystals. Click to zoom in and see.)

Notice how it has drained – the light color is due to the air underneath. The lines are roughly concentric with the shape of the puddle, though there can be considerable variation. On larger puddles or ponds, you might just see these thick curvy lines just near the shoreline.

Or around something that anchors (holds) the ice, like a tree or reed of grass.

Now the above two photos show both curvy lines and straight lines. I’ll just talk about the curvy ones here.

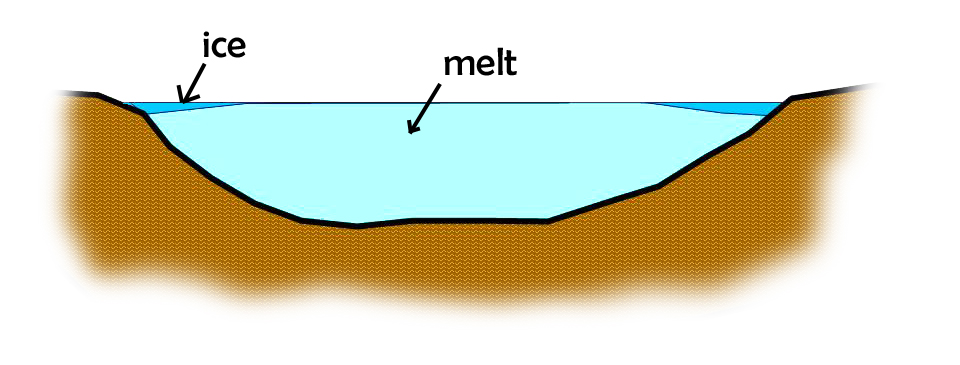

The thick, continuous curves show places where the ice is thicker underneath. Other lines may mark the boundary where the ice thickness changes. The ice thickness varies because of the way the meltwater drained below the ice. The sketch below shows a puddle just starting to freeze. We are viewing a cross-section, and the ice is coming in from the edge.

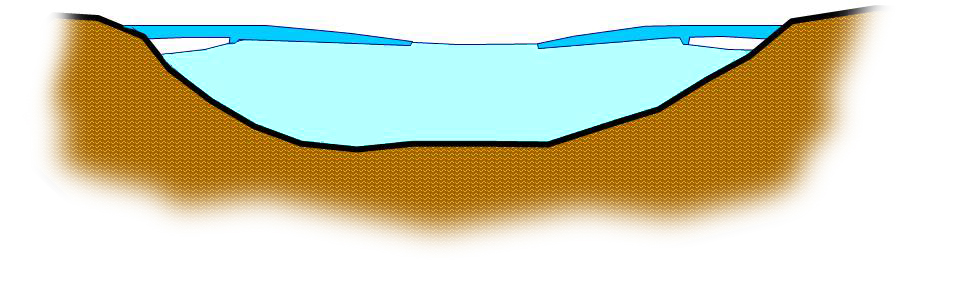

As the meltwater drains, it falls below the ice. But capillary, or surface-tension forces make the liquid melt cling up against the lower parts of the ice. It is like the meniscus around a glass. (If you put the bottom of a glass into a pan of water and pull it up, you will see how the liquid clings to the bottom of the glass. Same thing here.) So, as sketched below, a gap forms around the edge.

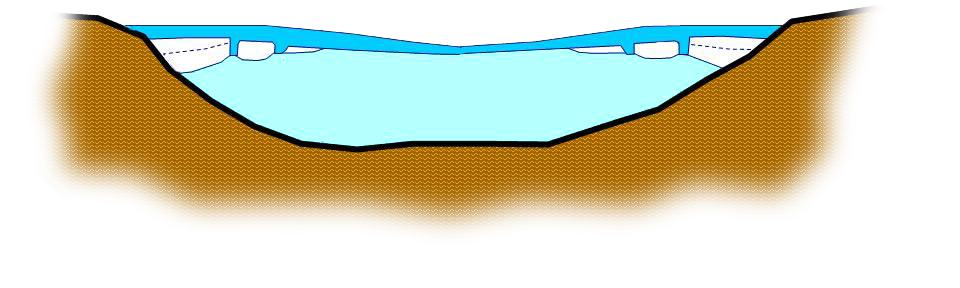

Ice grows down along the meniscus at the edge of the gap, and thickens wherever it presses up against the melt. The puddle continues to freeze over, but the melt has continued to drain. So, as sketched below, more gaps open up, roughly concentric with the previous gap.

And so, thin bands of ice grow downward where a meniscus of melt had touched the ice. From above, these bands of ice appear as lines, roughly parallel to the shore or whatever is holding the ice. The process I sketched above can continue to make more lines, and eventually, the water may drain enough to completely pull below the ice.

If you don't mind destroying nature's artwork for the sake of curiosity, break a frozen puddle and feel the ridges underneath. Sometimes they are very minor, hardly felt by your fingers, and other times, the bands may grow down an inch or more. The thinnest lines in the first picture are probably where the ice thickness just barely changes. But again, it is due to the curvy meniscus.

So that, roughly speaking, is how those curvy lines form. If bubbles of air had floated up, then they will also have a meniscus, and the meniscus lines will freeze into curvy lines too.

Frozen puddles are super common, but they are incredibly varied and often startingly beautiful. A whole Flickr photo group is devoted to them: http://www.flickr.com/groups/frozenpuddles/

Gaze at them for fun. Or better, snap your own frozen puddle shots.

-JN

4 comments

Hello Jon

I just started reading this blog it is very cool. I sent a copy of your book to my grandson Oren Nelson and am looking forward to reading it with him.

I hope all is well with you and your family

Regards

Andy

Hi Andy,

I bet you miss the ice and snow sometimes! Unfortunately, we haven’t had a frost day in weeks, and we haven’t had much sun either, just the usual NW winter rain. In Japan, we would often have both frost and sun.

Nice to hear about the grandson. Would like to see you guys together, reading about snow or otherwise.

Jon

Just thought I should tip you off to the reason for some extra recent traffic – a challenge issued by Professor Lewin, with this page listed as a providing a very good explanation. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B1QbNmCPgE0&ab_channel=LecturesbyWalterLewin.Theywillmakeyou%E2%99%A5Physics.

Thanks a lot, Jim.

Prof. Lewin sure has the mad scientist look about him now.

I did not know about the term “cat ice” for the ice on these “crunchy” puddles. The 1901 book excerpt that is briefly shown in that video gives the definition, but does not mention why cat is in the term. Online, the Merriam-Webster dictionary also gives the term “shell ice", and one twitter poster (@RobGMacfarlane) writes that the ice is just thick enough to “support a cat” and hence the term.

About that Prof. Lewin video, if you look to it for an explanation, then you can better use your time elsewhere–you will find no explanation there of any freezing phenomena.