Category: "Crystals on a capillary"

The Curious World of Ice and Snow: Part 3 of 3

February 8th, 2020These 14 slides are the final (third) section of my Science Cafe talk. (Plus two slides added as an introduction.) As in the previous section (previous post), this section mostly has ice forms that come from the melt, but the ice shapes here are a little "hairier". And at the end we return to forms influenced by the vapor. As with all these forms, I doubt any could have been predicted before their discovery. Nature is complicated, so Nature surprises us.

Click on any image to enlarge it.

As before, the green font below shows the content of this section. The first five cases involve melt flow along surfaces and in narrow pores. Remember that melt is another name for liquid. (The term melt is more accurate though, as it implies pure water, whereas liquid could be water mixed with any solute. For example, salt water is a liquid, but it is not melt.) As mentioned in part 2, their formation from the melt means that they tend to grow relatively fast and large.

First up is perhaps the most common. Do you know what is going on when the ground becomes crunchy?

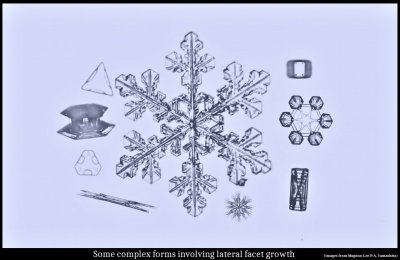

Some "Inexplicable" Snow-crystal Features: Applications of Lateral Growth

January 29th, 2020Last October, I gave a talk at the University of Washington about our recent experiments and ideas about snow-crystal growth. My pitch was general and short, as few folks work in this area and I'd hate to bore them with a long lecture. So, I was delighted to see quite a few graduate students in the audience, some of them asking good questions.

Instead of giving the narrated presentation here as a video, I will give the slides (23) with brief explanations similar to what was spoken at the talk. Narration below each slide. Skip to the ones that look interesting, and click on them to enlarge.

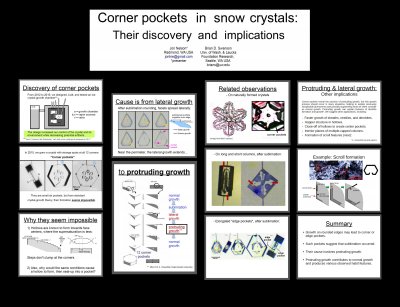

Poster on corner pockets in snow crystals

February 18th, 2019Last July, I attended the AMS (American Meteorological Society) 15th Conference on Cloud Physics, which was combined with a similar conference on atmospheric radiation. They have these about every four years, but I have missed all those going back to 1995. So, I had a lot to catch up on. Actually, by far the most enjoyable part of this conference was meeting old colleagues and making new acquaintances, including many who I had known only through their papers and email correspondence. As to why I waited so long, I suppose the main reasons were time and cost. Even without travel and lodging expenses, conferences are expensive. This one was $600, and the fee for the abstract I submitted was an additional $95. But in this case, the conference was only a 3-hr drive away (Vancouver, BC) and my co-worker very nicely picked up the conference fee and hotel tab. Also, this conference had a special session dedicated to the work of my former advisor, Prof. Marcia Baker. In that session, I presented the following poster.

I've described a little about corner pockets in a previous post, and showed a few of these panels before, but will briefly go over them here.

Akira's Corner Pockets

May 10th, 2016The evanescent snow crystal

appears out of nowhere

The lines and boundaries

on its faces record a story

a story of a crystal's birth

a story of a crystal's life

But before the record vanishes

Who will hear its story?

A few years back, a correspondent of mine, Professor Akira Yamashita of Japan, long retired, sends me an email. In the email, he had a document with words and pictures of some small crystals that he'd captured back in the 70s. They were small crystals, essentially freshly "hatched eggs" from the frozen droplets upon from they had started. But some had small pockets of air near their corners.

To those who have studied any sort of crystal growth and have some familiarity with crystal-growth theory, these corner air pockets, or "bubbles", were in impossible locations. They should not be there. Pockets will form near face centers, not corners. But Prof. Yamashita also had a theory about their formation. His theory first looked sketchy to me, but I appreciate hearing about new ideas, so over the following years kept revisiting his theory, getting to think that it had merit, and wondering if it had other applications.

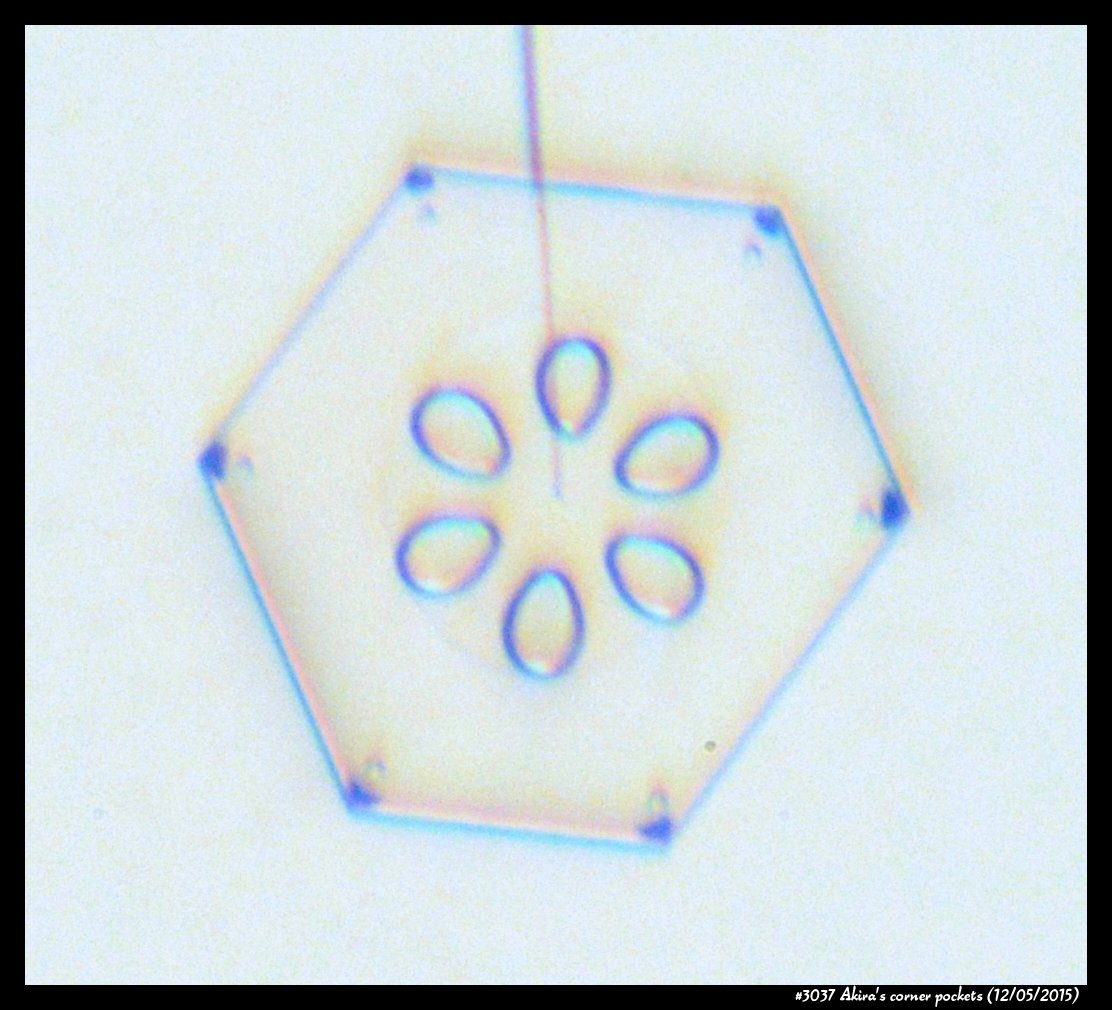

Then, just this past year, in our own ice-crystal experiments, we did something that apparently had never been done to small ice crystals in the lab before. We slowly grew a crystal in air. And we cycled it from slightly growing, to slightly sublimating (i.e., shrinking in size), to slightly growing again. A cycle that must happen in some regions of cloud. And here is what we saw:

Corner pockets!

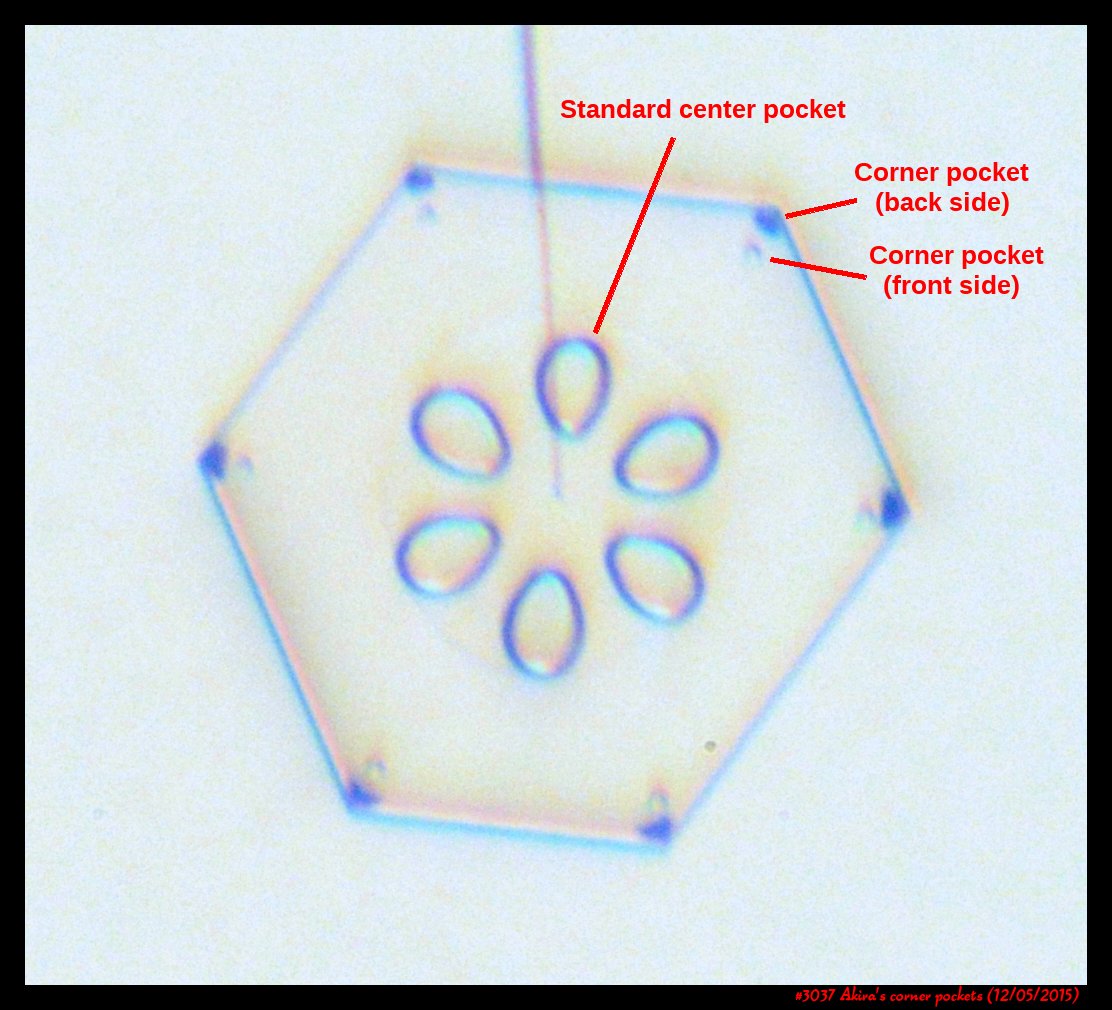

After the sublimating, the subsequent growth kept a permanent record of the sublimation cycle in the form of 12 corner pockets, one pocket for each of the 12 corners of the crystal. These are pockets of air, just like the six large 'petal-shaped' pockets of air you see nearer the center of the crystal. They are forever stuck in the crystal. Stuck there until the crystal, with all of its features, vanishes back to air.

After seeing this, we ran a few more experiments, and each time we slowly grew, then sublimated, then grew again, we got corner pockets. The name 'corner pockets' refers to their location when they are formed; namely at the corners, next to the crystal perimeter. However, they remain essentially fixed in position as the crystal grows, and this means that as the crystal perimeter expands outward, the corner pockets will appear further within the crystal. Analogously, the 'center pockets' shown above formed at the face centers, on the crystal perimeter, back when the crystal was much smaller.

As to the theory of their formation, and how the theory can explain other observable features of snow crystals, you'll have to wait for a subsequent post.

- Jon

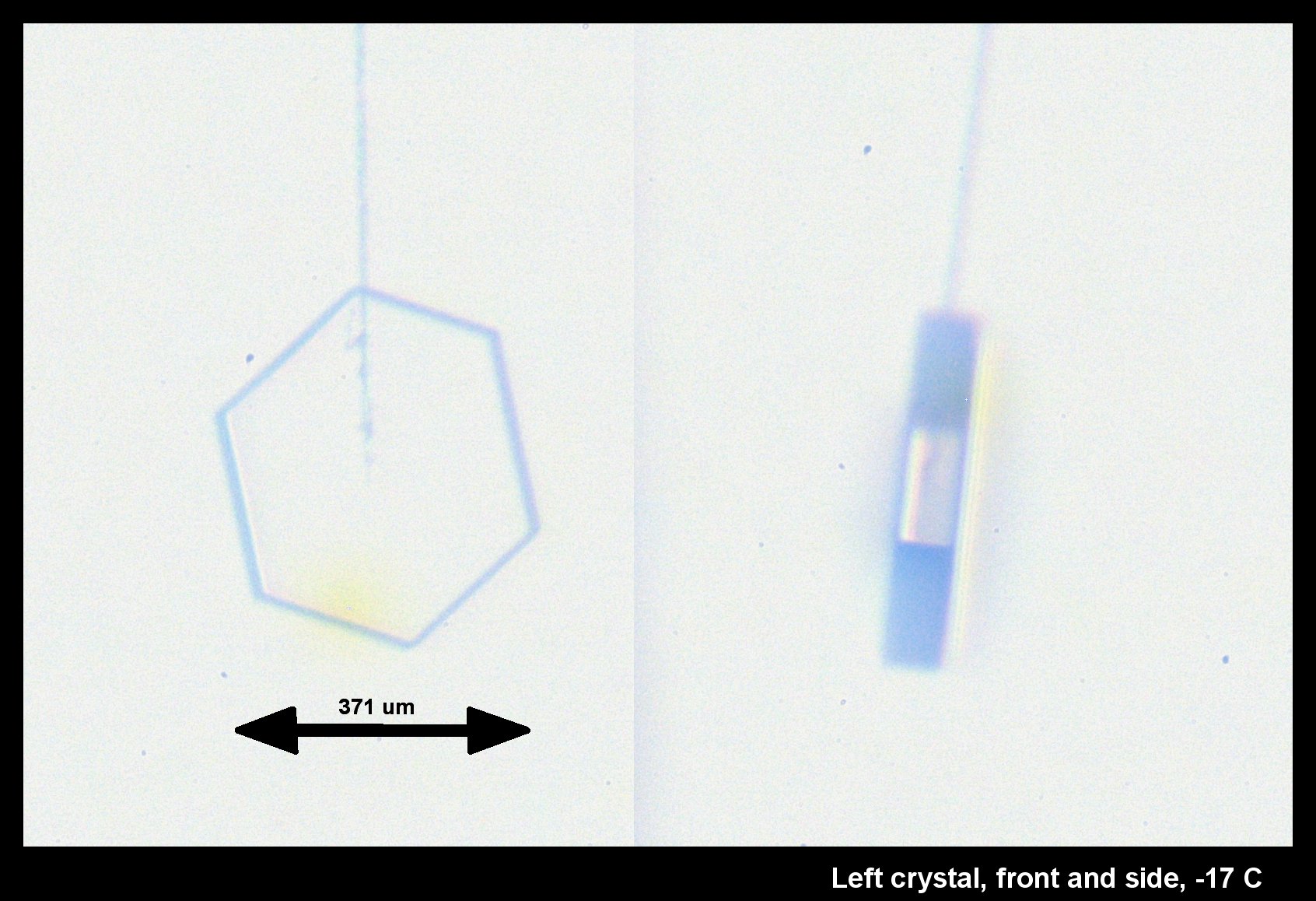

Standard P1a Hexagonal Crystal, Front and Side

December 19th, 2014It didn't start so symmetrical, but became so as it grew:

This, the left crystal of the pair described two posts below, grew much more slowly on its basal faces (front & back in the left image). The way it grew, and its big difference with the crystal on the other capillary (described two posts below), indicates crystalline perfection on the basal faces. Imperfections on the other crystal caused its basal faces to grow relatively fast.

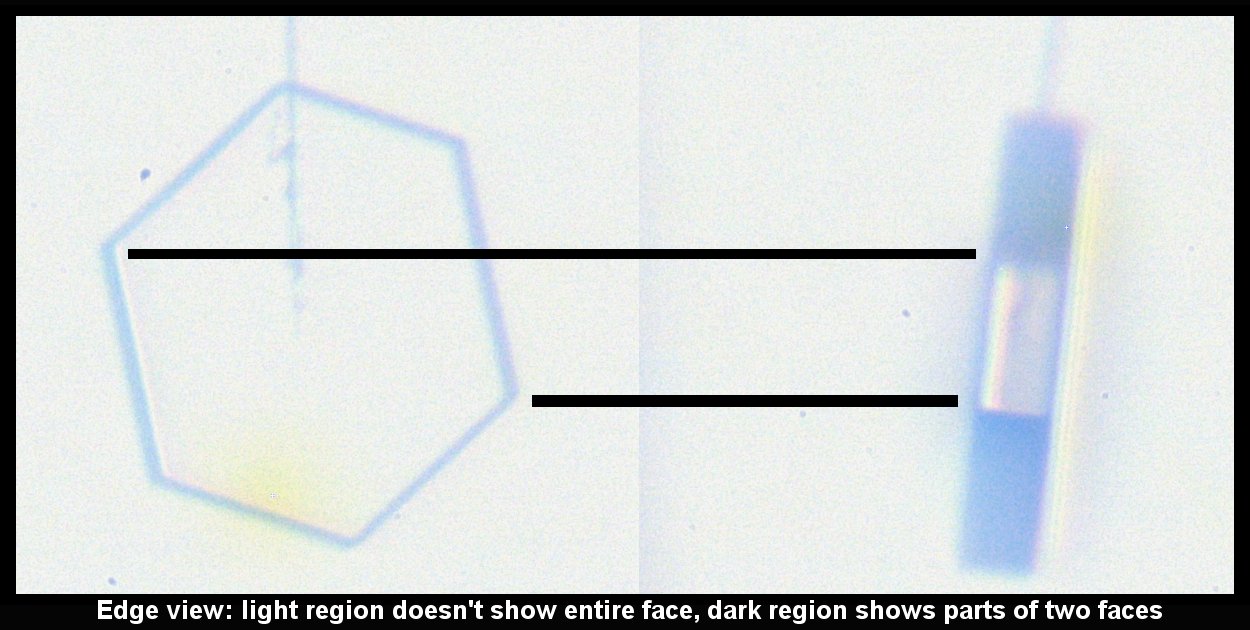

The bands of dark and light on the rotated crystal (right side above) suggest different facets. But the light regions are instead regions where the light, coming from the back, can go through two parallel (or nearly parallel) faces. Thus, the light region is actually less than a complete facet, whereas the top dark region is a combination of two facets. See the facet-by-facet comparison below:

--JN

A Crystal Pair, Several Views, and a "Man on the Crystal"

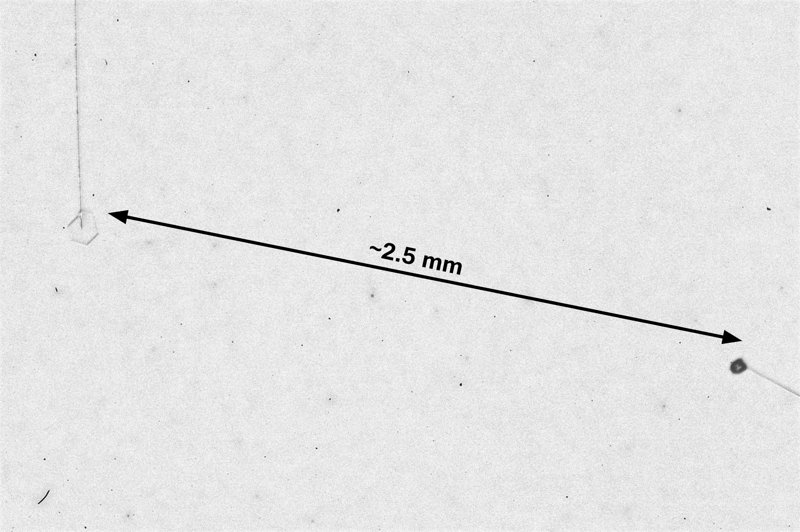

December 19th, 2014One advantage of the new apparatus is the capability to grow up to three crystals at a time, each on its own capillary. It is also very useful being able to move each capillary around. Having success with a single crystal, we tried it with two, and much thinner, capillaries.

This time, we had to cool the apparatus down to about -38.5 C before they appeared (previous cases were about -20 C), and to my surprise, they both appeared at about the same time. (Polycrystalline blobs, as are more common at these low temperatures.) Due to some troubles we were having with the vacuum (later discovered to be simply a case of the pump getting shut off), we warmed the crystals up to -17 C, sublimated them, and regrew them.

The capillaries slide up-down on axes that intersect, designed this way so we can bring the crystals nearer or further apart. For the above image, they were relatively close. The crystal on the left is a thin plate, whereas the one on the right appears to be a short column. Both grew under the same conditions, but grew into different forms.

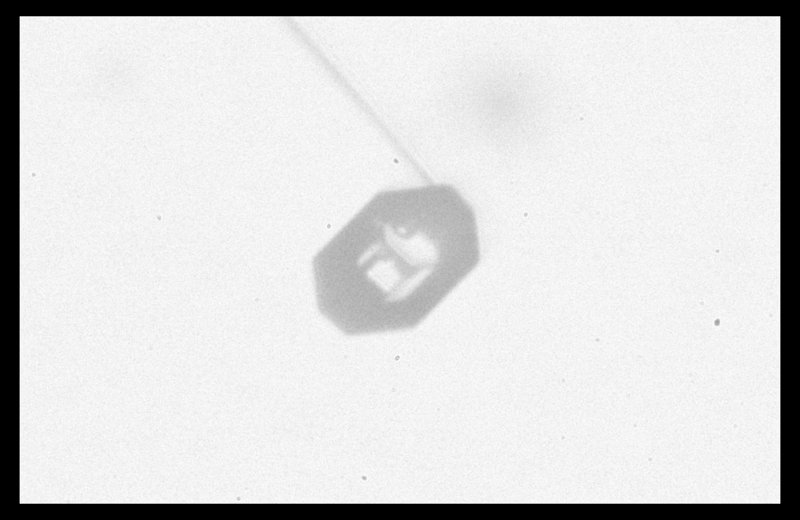

On closer look, the rightmost crystal revealed itself to be more interesting than initially thought:

The apparent "man in the crystal" (i.e., face, as in the "man on the moon") shown in the view above arises from dark lines, which are due to face-face edges on the other side of the crystal, a horizontal "terrace", also on the other side, plus an air pocket inside the crystal.

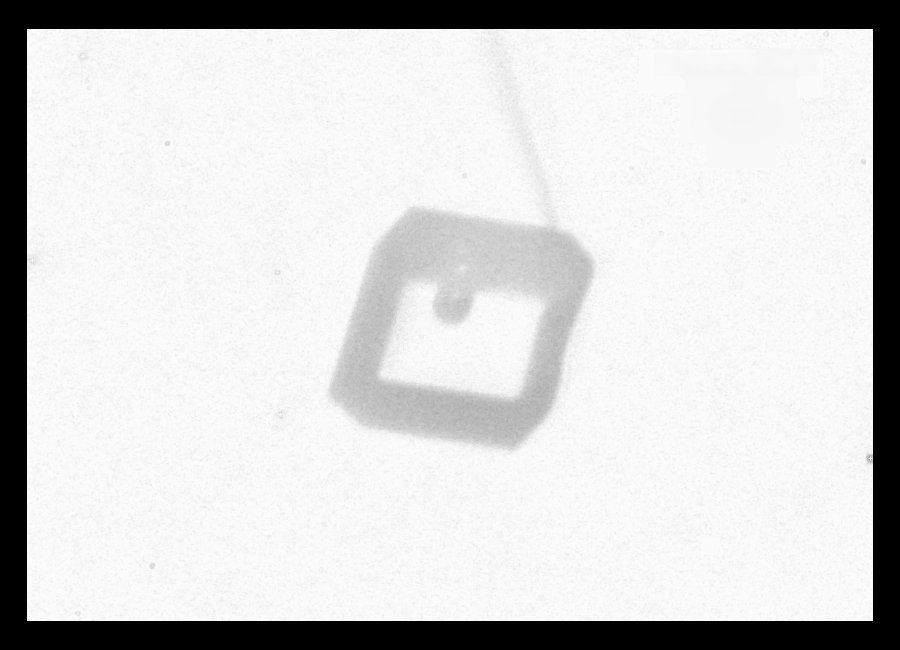

Also, the crystal appears to be eight-sided around the perimeter, but this is again an illusion due to perspective. Rotating the crystal around the main capillary axis instead suggests a four-sided form:

Whereas another rotation suggests a common hexagonal prism:

The horizonal extent of the crystal is about 150 micro-meters (microns). The view above clearly shows the interior air pocket. Also, on the right, you can see the profile of the "terrace" mentioned above.

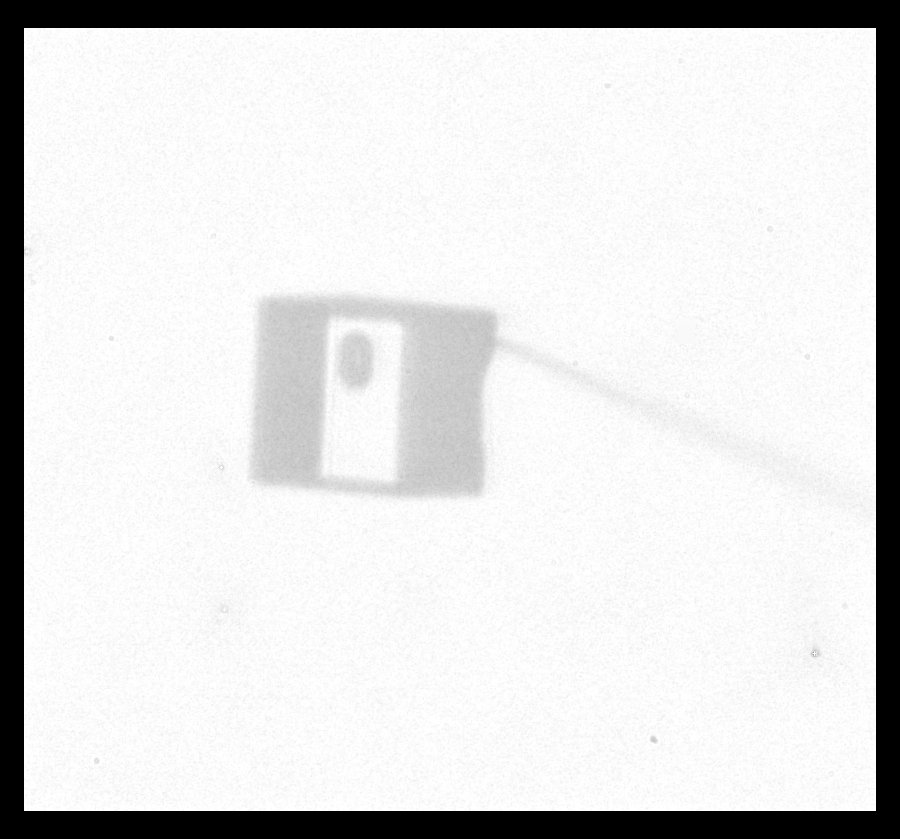

Another rotation, giving another view, helps to clear up the mystery of the 3-D crystal shape:

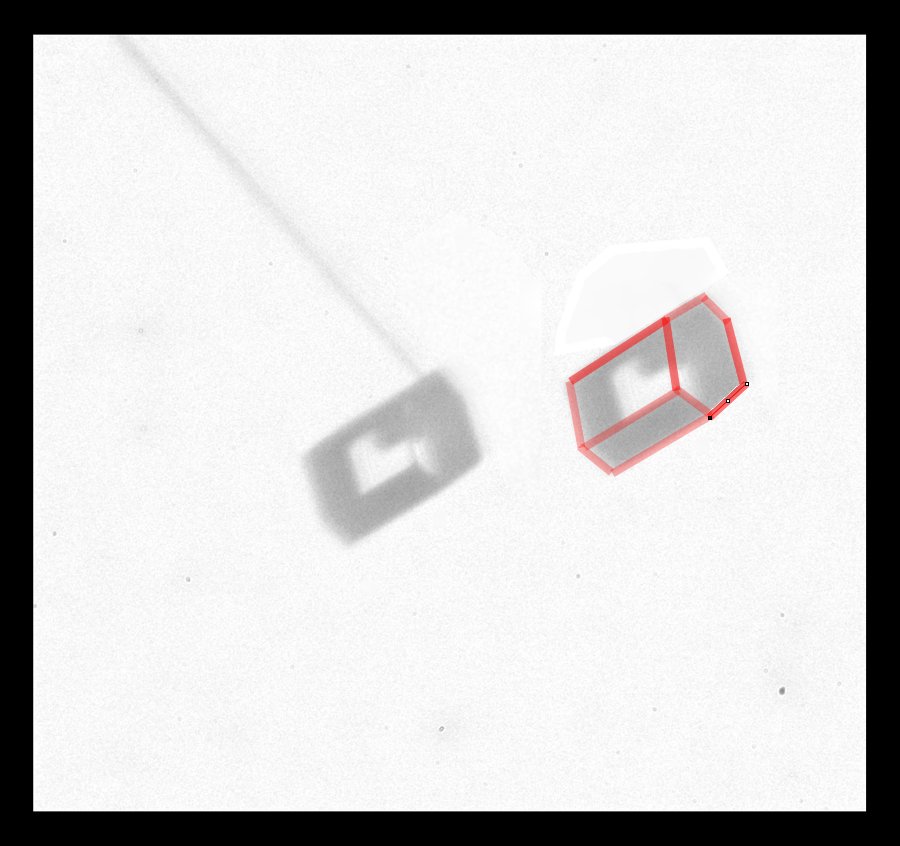

The crystal is a short hexagonal column, but two opposite prismatic faces are much larger than the other four (because they grew much slower). I copied the crystal image at right and outlined the crystal edges in red. This shape of crystal is thought to give rise to one of the "Parry arcs" in the sky, which I showed in an earlier post.

Another interesting thing about this crystal is its very weak attachment to the capillary. The molecular forces holding it up were so weak that torques arising from the pull of gravity would cause the crystal to slowly rotate downward. In general though, these cases show how useful it is to be able to move and rotate the crystals.

--JN

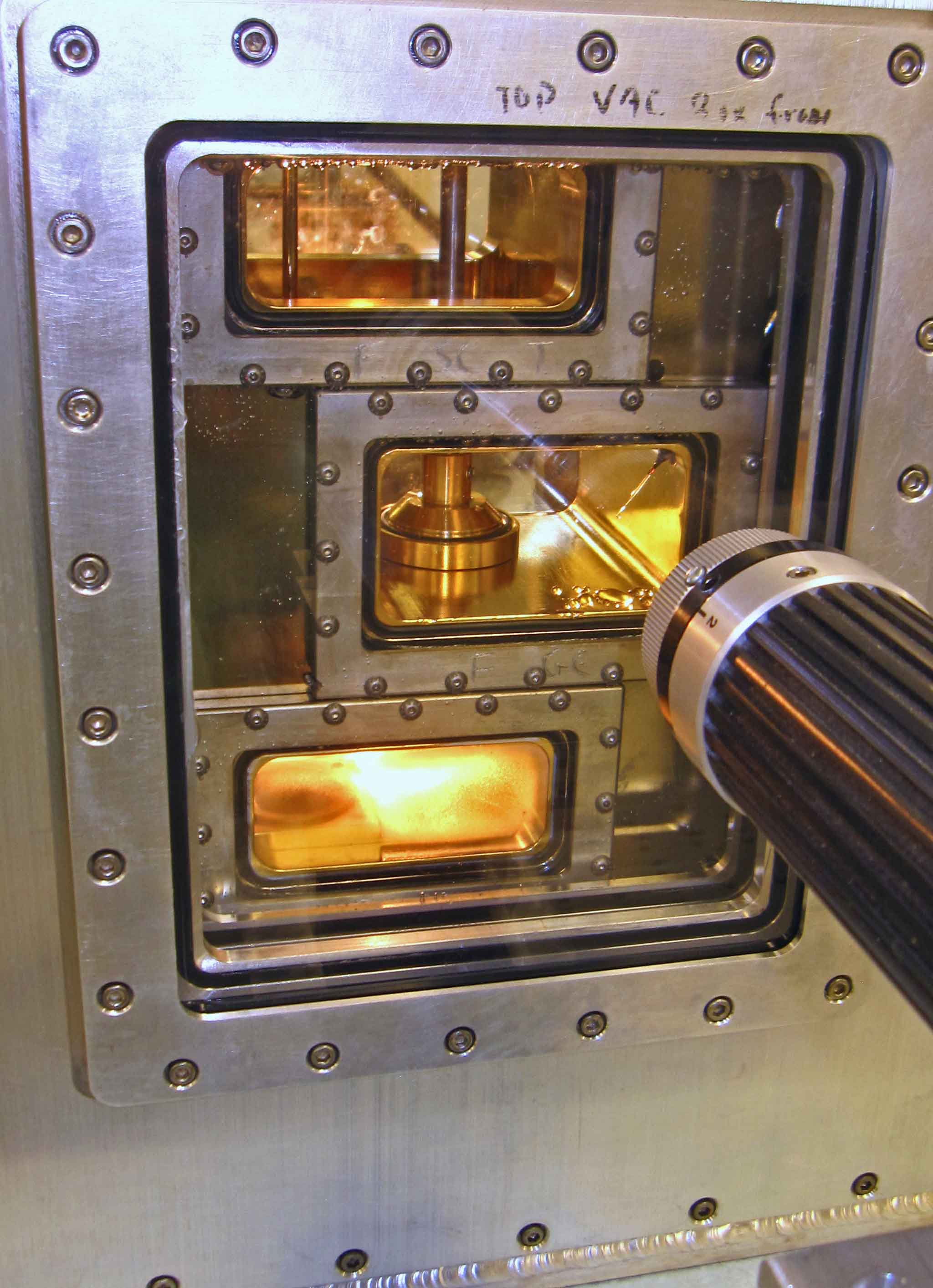

New Capillary Crystal-Growth Device

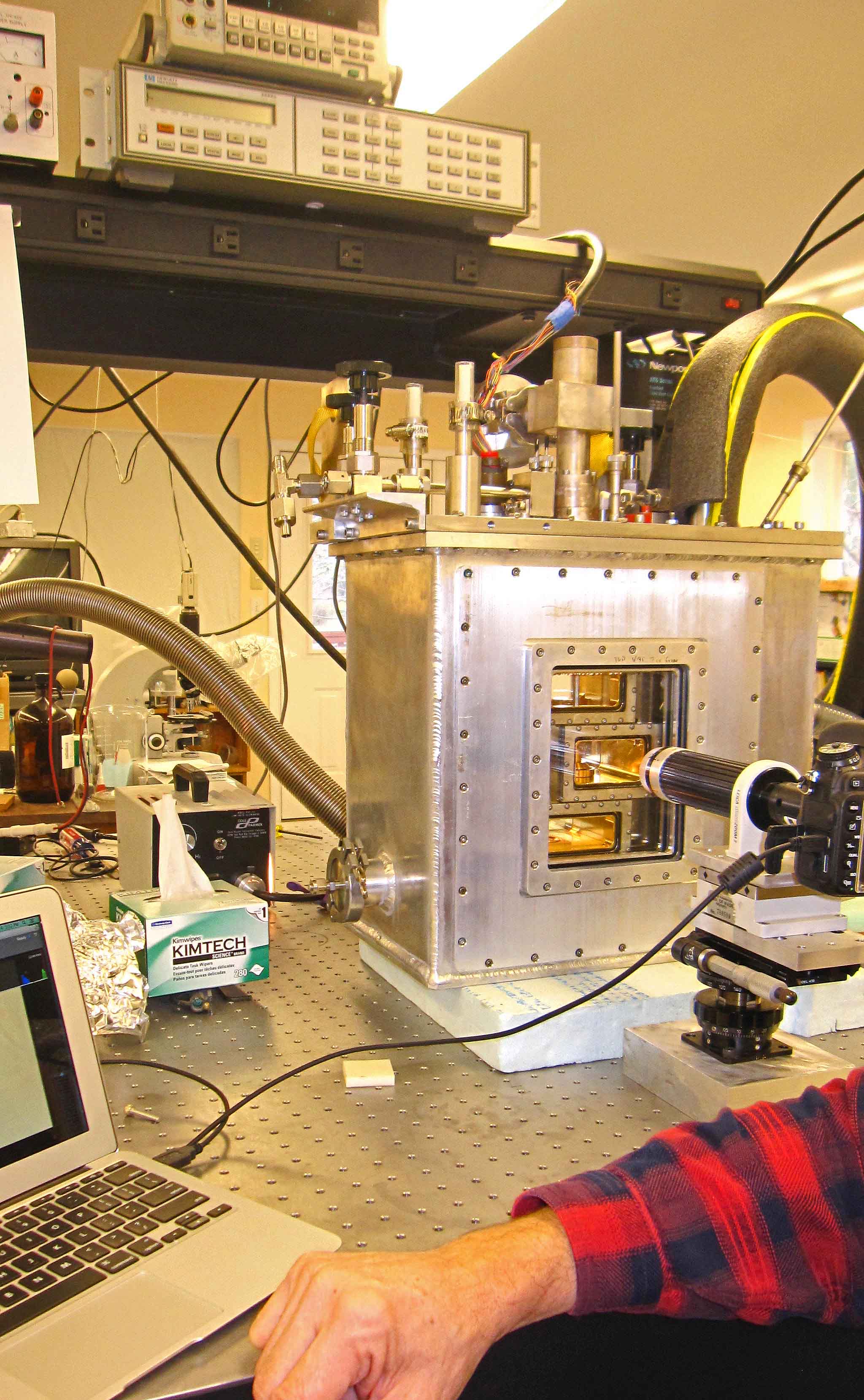

December 11th, 2014After several years of planning and several more years of construction, our new crystal-growth device is operational. We are now tuning the electronics, vacuum system, data collection method, and other aspects, but we can indeed produce ice crystals on a glass capillary under controlled conditions.

The thing works!

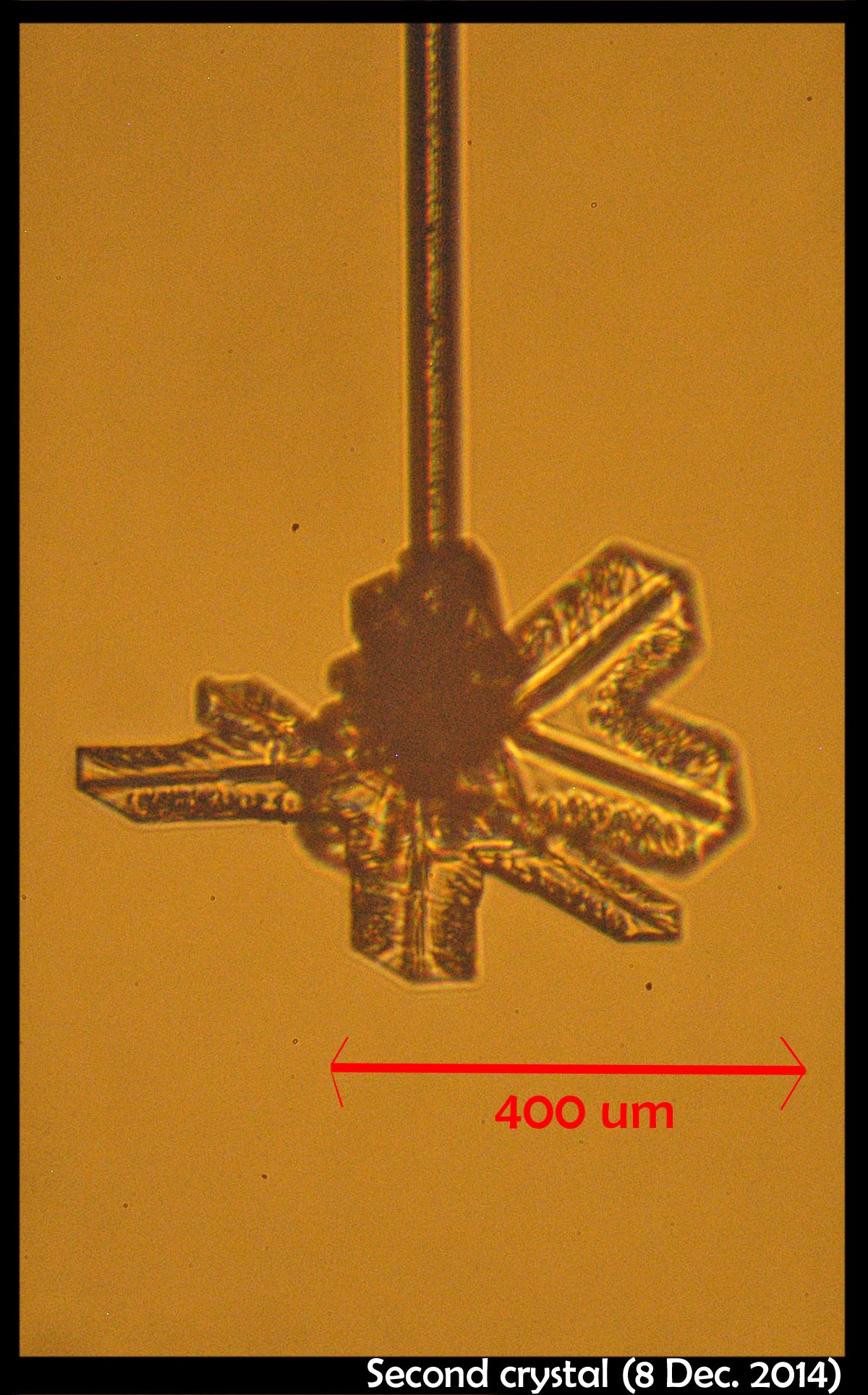

The first two capillaries we tried basically exploded, due to my having loaded them with way too much water, but the third produced a nice frozen droplet. The frozen droplet, or "droxtal" did not grow on account of all the water that had spewed down from the previous attempts, but we cleaned up the debris, and started anew. That case, pictured above, produced a nice spatial dendrite. I could control the growth condition quite well, and kept growing, sublimating, and regrowing the same crystal for a few days. We now need to refine our capillary-making method and make them about 10x thinner (as I used to do in my previous experiments).

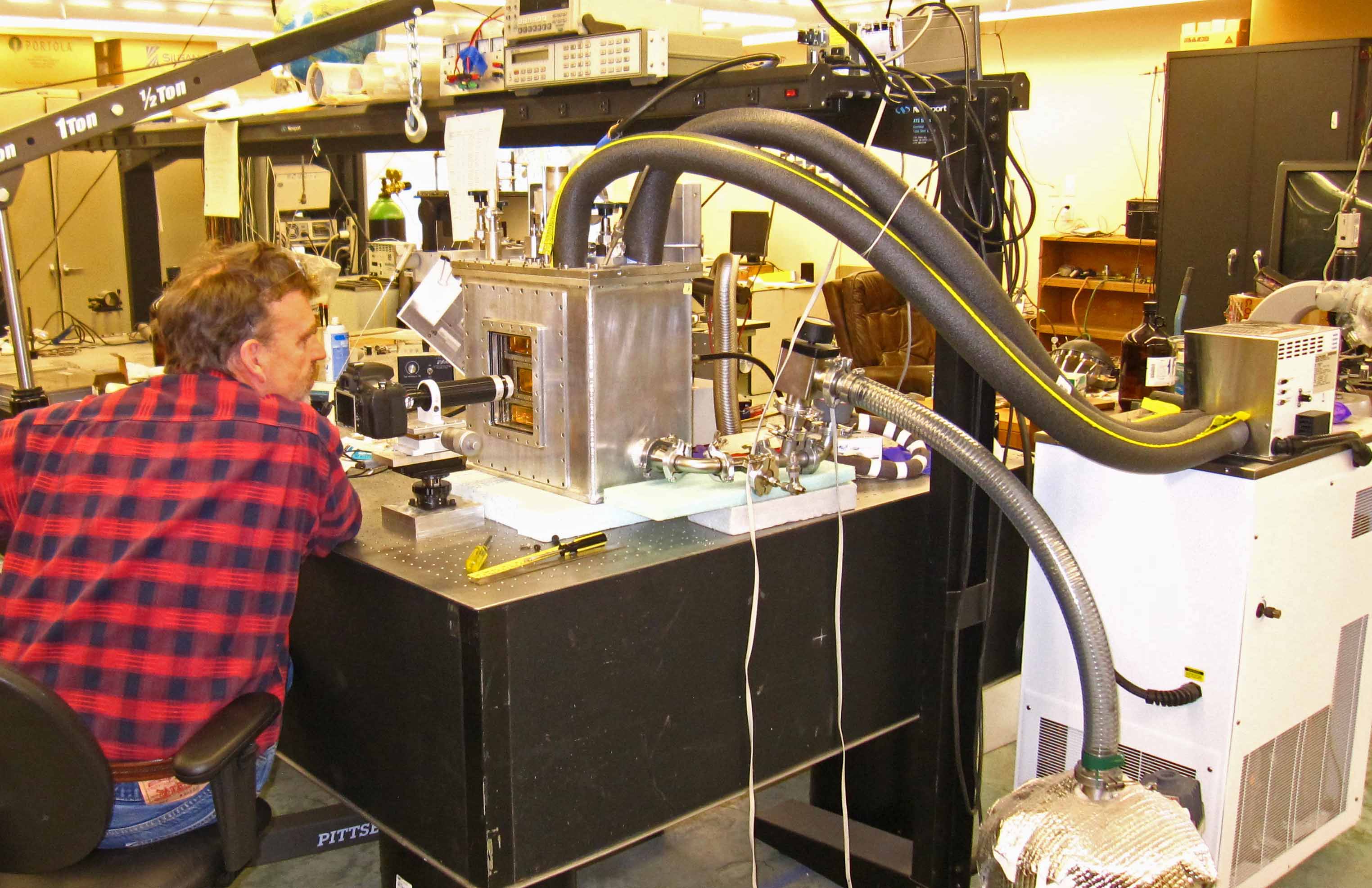

The overall setup is pictured below, Brian at the controls.

The white thing on the right is the cooler. It pumps cold methanol into the big aluminum box sitting on the table. That box is actually three boxes: an innermost crystal box (consisting of several chambers), a bath box that holds the cold methanol cooling fluid, and a vacuum box around that to help insulate the system.

All the controls enter from the top, so we have lots of things sticking up on top: fluid in-out ports, vacuum control of the growth chamber, reference chamber access, access to two vapor-supply chambers plus vacuum control of the chambers, a valve system to connect vapor to growth chambers, and a bunch of wires... The inside of the innermost crystal box is gold-plated to deter corrosion and help us keep contaminants to a minimum.

We hope to have more crystal images soon.

--JN

The fun of shooting down your own theories

April 10th, 2014Thomas H. Huxley once wrote the famous line:

The great tragedy of Science: the slaying of a beautiful hypothesis by an ugly fact.

Great man, catchy phrase, but perhaps a bit overdramatic. To me, the slaying of a “hypothesis” (i.e., pet theory or just idea, really) can be the beautiful thing. It means that one can do a lot of damage with just a simple observation. I like it, even when I'm shooting down my own theory. Here's an example:

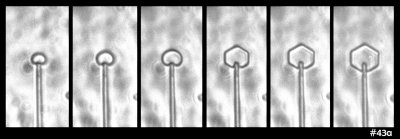

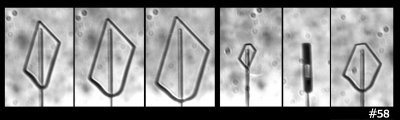

Some time ago in my experiments, I saw the following ice growth sequence:

What you see there is an extremely small, thin ice crystal growing from the tip of a glass capillary into air. (Size-wise, the glass capillary is about 5 micro-meters in diameter, or about 1/10th the thickness of the hair on your head.) I saw it happen several times. As the crystal grew, it developed the prism facets that generally define the hexagonal crystal shape. Other people had seen such rounded growth before, generally within a few degrees of zero (C), though in all cases, the crystal had been extremely thin. You can also see this thin, rounded (non-facetted) form in some hoar-frost formations.

The mystery here is why the disk grows without the prism facets for awhile. I never saw this with thicker crystals, so I formed a little theory. The theory involves the source of the water molecules to the curved region of crystal: some come from the vapor in the air and some wander over from the flat, non-growing crystal faces on front and back. In the 1960s, people had tried to measure this “wandering distance”, but never determined a consistent value. My theory predicted that once the crystal thickness exceeded about twice this distance, the curved edge would transition to flat, giving rise to the hexagon.

But then I looked closely at this case:

That sequence shows the side and front view. The crystal doesn't discernibly thicken when the flat prism facets appear. Zing! That theory shot down.

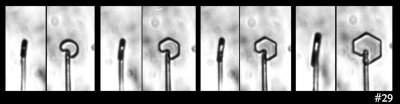

On to the next pet theory. So maybe the key factor is the diameter of the disk: One might argue that the curvature of the crystal surface must be below a certain value, which means a large enough diameter is needed, for the flat facets to appear. Or, the size of the resulting prism faces must be larger than that needed to have several surface steps (which help ensure flatness).

But then I look at this case:

In that case, I see both smaller and larger prism faces forming at the same time (same thing can be seen in the previous image). So, I guess the curvature or size of the resulting face is not the main factor. Zing!

Some researchers had observed slight bending of the prism facet above -2.0 C in equilibrium. They postulated a “roughening temperature” at -2.0 C. This might explain the rounded disc edge, but wait! 1) This disc edge becomes facet as it grows, so it is not merely temperature, and 2) these crystals are below -2.0 C.

Zing again!

Well, there are always “impurities” to blame! Crystal growers are fond of blaming some trace, active chemical, or “impurity” for inexplicable results, so we could theorize that the above show the effect of surface impurities. As the crystal grows, the area over which the impurities distribute increases, thus diluting their concentration, and thus reducing their effect. Yes! This could explain these results.

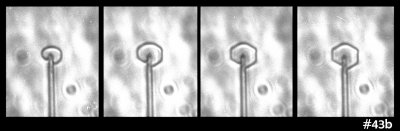

But, wait, what about this:

The above shows two sequences (same capillary) in which some prism facets have formed, but some remain round. In the right-side case, one corner even rounds as it grows. Hmm, not a likely result of impurities. Zing!

So, I am down to one last theory. I do not yet have the data to shoot it down. And I'm not telling you, or I'd ruin the fun. We just need more data.

All in all, I think Huxley needs a little tweaking to serve my view:

The great beauty of science: the slaying of a pet idea by a simple observation.

-JN