Category: "Rime ice"

The Snowflake’s Closest of Kin

February 21st, 2022[From 2006 through 2012, I contributed annual articles to the annual newsletter "Snow Crystals" for the Wilson Bentley Historical Society. That newsletter is no longer available, so I will repost my articles here, starting with this one from 2006.]

Wilson Bentley is well known to readers here for his photomicrographs of snow crystals. Snow, however, was only one of the many ‘water wonders’ that held his fascination (ref. 1). Some of these wonders were made of liquid water, such as dew, and some, like the snow crystal, were frozen water (ice).

The frozen type he called “The snowflake’s closest of kin”, and they included hoarfrost, rime, windowpane frost, and ice flowers (2). To obtain photographs of any of them with the quality obtained by Bentley is difficult even now, which is yet another reason to admire Bentley’s skill and perseverance.

On the inside, these ‘kin’ all have the same crystal structure. But they appear different on the outside, largely due to the different ways the water in the surroundings gets to the ice surface. There are many distinct kin because the surrounding water can be in various states (i.e., ice, liquid, and vapor) and there are many ways that each state of water can get to the ice surface. I’ll focus here on snow crystals, hoarfrost, rime, windowpane frost, and ice flowers. These forms are commonly seen by many of us, and have been observed by people for a very long time. So it is easy to think, as I probably once did, that they are well understood by science. But this view is quite mistaken. Yes, we know they all consist of H2O molecules and we know something about the structure of ice, but how exactly they form contain many mysteries. I’ll describe briefly what Bentley thought of them, and what I think is known and not known about them.

The Curious World of Ice and Snow: Part 2 of 3

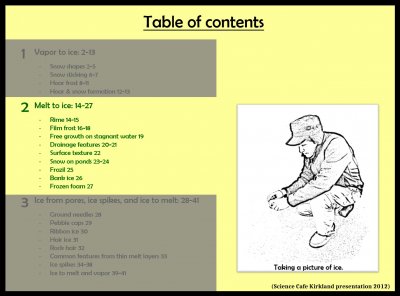

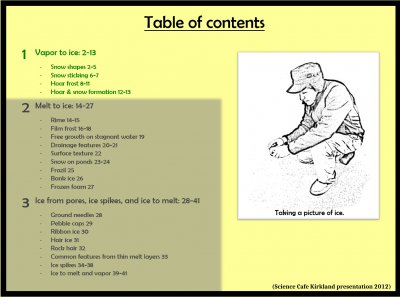

February 8th, 2020As I mention in Part 1, these are slides I gave for a Science Cafe discussion session in 2012. This section focuses on ice that forms directly from the melt, that is, the liquid phase. Contrast these cases with those in part 1 in which the ice grew from the vapor. Some of these cases might seem a little familiar, but many ought to seem downright bizarre.

As always, click on an image to enlarge it.

The contents here are emphasized in green font below. The underlying difference between ice growth from vapor and from melt is that the melt is much denser. The higher density means that vastly more water molecules can impinge on the ice surface in a given time and area. This higher impingement usually means faster growth and larger crystals, but the way that the melt reaches the crystal influences the form, and the result is not always so obvious. In fact, I would even say that it is never obvious.

OK then, let's get right back into it.

The Curious World of Ice and Snow: Part 1 of 3

February 4th, 2020In 2012, I gave a "science cafe" talk with a local series sponsored by the Pacific Science Center, KCTS public television, and Science on Tap. The title was "The curious world of ice and snow". The location was a bar in Kirkland, but open to all ages. When I showed up with my family, they tried to seat us in the backup room, the regular room having filled up, but I said "Oh, well I'm the speaker" and they kindly created a space for my family in the regular room. I was indeed surprised at the crowd. People are apparently more interested in ice than I thought. (Hmm, but where are they when I post here?)

Click on any image to see an enlargement.

The basic structure of each talk was to give a lecture of about 30 minutes and then allow up to an hour (I think) for the Q&A. In my excitement, I had created 41 slides, in retrospect too many for the allotted time.

Given all the time spent preparing the slides, I hope that by posting them here that even more folks can enjoy the images and discussions. But, instead of unloading all of them on you at once, I will break the discussion into three sections. By adding the following table of contents, each section will have 14 new slides and the total will be 42, which according to Douglas Adams* is a really special number.

The contents of this section is part "1", written in green font.

How clouds form snow

January 14th, 2017To understand snow formation, one must know a little about clouds.

Q: What is in a cloud?

A: Air, dust, vapor, droplets, and often, ice.

Q: How much air? How much liquid water? How much ice?

A: The answers will probably surprise you. See my short 20-min presentation below. I gave this recently to the Bellingham, WA Snow School. (23 slides, but due to file-upload-size restrictions, I had to put them into three parts below, 10 slides, 6 slides, 7 slides.)

Snow, rain, and weather affect everybody, yet how many of us learned in school even the most basic facts about precipitation in school?

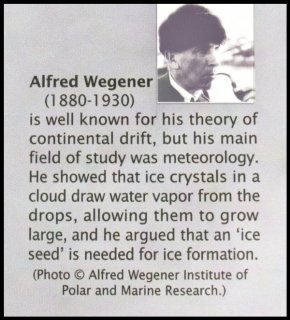

Q: Who first realized how ice grew in a cloud?

As described in my presentation, he realized this by observing frost on the ground.

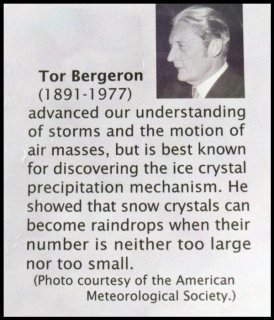

Q: Who first realized how Alfred's theory was intimately connected with rainfall?

Tor discovered this by observing fog in a mountain forest, and like Alfred, applied some of his physics knowledge.

In my presentation, I discussed Alfred Wegener, the roles of the different cloud components, and briefly how the ice, once formed, takes on its strange shapes:

First 10 slides (with blue text added to account for the things I said during the talk):

http://www.storyofsnow.com/media/blogs/a/Jan2017/snowschool_annotated1t10.pdf?mtime=1484585328

Next 6 slides:

http://www.storyofsnow.com/media/blogs/a/Jan2017/snowschool_annotated11t16.pdf?mtime=1484585328

Last 7 slides:

http://www.storyofsnow.com/media/blogs/a/Jan2017/snowschool_annotated17t23.pdf?mtime=1484585309

Later, I will show specifically how the ice gets arranged into all these strange shapes.

- JN

Glaze-rime Ice Buildup Facing Creek

November 23rd, 2014Here's a reed of some sort, with a glaze of clear rime on the side facing a creek. How did the clear ice get there, and what is the white ice on top of it?

The fact that the clear ice is just on the side facing the creek indicates that the ice came from droplets blown off the creek. To have the ice buildup just on the side means that the droplets must have frozen soon after landing, but slow enough to spread out and fill gaps.

So, the droplet must have been larger than typical cloud droplets, and the temperature must have been within a few degrees of freezing. Clearly, the flowing water must have been above freezing, so the droplets must have cooled to below zero while drifting through the air.

A closer shot shows that the outermost ice, the white ice, is hoarfrost. Only hoarfrost would show the flat crystalline facets. Definitive proof that that ice grew out of the vapor that was blowing by. You can also see some hoar on the other side of the reed.

--JN