Category: "Weather and Climate"

A greenhouse effect demonstration that you can feel with your hand

January 18th, 2023Probably most people consider the greenhouse effect as an important, yet subtle, effect on our climate. I suspect though that very few consider it the major effect on our daily weather, amenable to direct sensation, that it really is. Perhaps this lack of appreciation can be partly alleviated with a simple and quick demonstration. Below is my attempt at such a demonstration. This demo focuses on a key aspect of the greenhouse effect. It requires only items typically found in a kitchen yet allows one to directly feel the warming. An added bonus is that the specific phenomenon illustrated also helps explains other phenomena we witness in daily life. Below are all the things you need to do the demo. (click on any pic to enlarge)

What does the greenhouse have to do with snow?

But first, as this is a snow blog, what is the connection to snow? The growth of snow crystals is, except for their being in free-fall, almost exactly the same as the growth of hoar frost on the ground. The hoar frost on the ground occurs when the local greenhouse effect during the evening and night is relatively weak. That is, the local atmosphere above is cloud-free and relatively dry. (Of course, the air at the ground needs to be relatively cold and humid as well.) This connection illustrates one way we directly sense variations in the greenhouse effect through our weather. More on this later.

A key aspect of the greenhouse effect

The greenhouse effect involves several connected concepts, or aspects, a fact that makes the complete effect much more challenging to understand than is commonly appreciated. Nevertheless, we can readily understand one of its crucial aspects: emitted infrared radiation (IR) from the atmosphere directly warms us on the ground. This IR radiation from above, also known as “back radiation”, is not small: indeed, averaged globally and annually, the radiated energy we receive from atmospheric IR is roughly twice that which comes from the sun. (Why do we not notice such a large effect? Because, unlike sunshine, it never stops.) Unfortunately, this is not how the effect is usually presented in the popular literature. For more details about this issue and other greenhouse misconceptions, I urge you to read Alistair Fraser’s excellent and amusing “Bad Greenhouse” page (1), but here I focus on a simple demo.

Simple demos of the effect

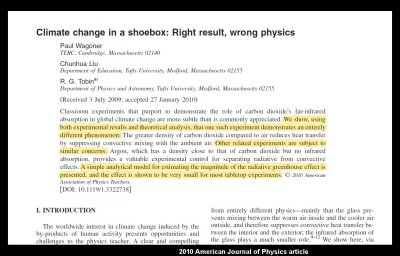

Most demos of the greenhouse instead focus on atmospheric absorption of infrared by greenhouse gases. Although absorption of IR is part of the greenhouse effect, to understand how we are warmed at the ground, one needs additional concepts to complete the explanation, concepts that are usually left out of the discussion. More to the point for this blog entry, of the demos that I’ve seen, all of them misrepresent the atmospheric greenhouse. Specifically, instead of illustrating a heating process in the atmosphere, such demos instead illustrate the heating process in a gardener’s greenhouse. This is the wrong effect. If you are skeptical of this claim, consider the highlighted text in the following study (2):

A similar study was published a few years later in the European Journal of Physics. But it is not just the physicists who think the popular demos are wrong, here is a similar study from chemists (3):

The title of that study should also make their point clear. Let me emphasize here that the demos that these studies criticize are actually the best available ones, for example the one use by Bill Nye, “the science guy”. A quick survey of other demos readily found on the Internet (refs 4-7) takes me to ones that are even less relevant to our atmosphere (sadly, even ones suggested by NASA). It is also unfortunate that even the above two studies use terms "climate change" and "global warming" in their titles, even though they are really about the greenhouse effect. These are distinct concepts, the former being about an increase in the latter. We are interested here only in the greenhouse effect.

As pictured in the first image above, all you need for this demo is a stove (or hotplate), a baking pan (if using the stove), oven mitts, new aluminum foil, a baking sheet (i.e., oven-safe paper), and a few teaspoons of vegetable oil. For extra safety, use protective eyewear. Total time needed once you have the pieces set out, is only about 15 minutes. No thermometer is needed because you can feel the warmth with your hand.

1) Set the baking pan on the stove burner, centered if possible.

2) Put a little vegetable oil in the center and press on a section of aluminum foil to cover the base of the pan as completely as possible (can extend over the edges). Use an oven mitt to press the foil flush against the pan.

3) Turn the burner on to “medium” and wait about 10 minutes for it to heat up.

4) While waiting for the burner to warm up, tear off a piece of baking sheet large enough to nearly fill the area of the pan. Set it aside.

Once the pan has warmed up (carefully touch an edge of the pan to check), the experiment begins.

A) Put your hand a few inches above the center of the aluminum foil. Does it feel warm? WARNING: NEVER TOUCH THE FOIL SURFACE! IT IS VERY HOT!

B) Now put a little vegetable oil on the aluminum foil and carefully drop the baking sheet on the foil, trying to set it down without touching the hot surface so it covers nearly all of the foil. With the oven mitt on your hand, quickly press the baking sheet down so there are no air gaps between it and the foil (this is the purpose of the oil).

C) Now, repeat A). Does it feel noticeably warmer? (Before the baking sheet starts to burn, please use the mitts to move the pan off the burner and turn off the burner.)

It seems weird that you can put a cool object (the baking sheet) between your hand and a hot surface to actually warm your hand. Nevertheless, your hand is warmer because the baking sheet is an effective radiator of IR, whereas the Al foil is a very poor radiator of IR. (This is why hot items are wrapped in foil to stay warm.) For this reason, the adding of Al foil to the pan likely made the pan even hotter--it reduced the capability of the pan to cool. With the oil between the pan and foil, and between the foil and baking sheet, all three were put in good thermal contact, exchanging heat via conduction and thus having essentially the same temperature. However, the the top layer (i.e., the foil in A, the baking sheet in C) cools by conducting to the air above, so the top surface will actually be slightly cooler than the pan. However, in general, the temperature of a hot object mostly cools by emitting IR, unless it is covered by a poor IR emitter like Al foil.

In this experiment, it is too easy to be fooled into thinking the foil is not hot because it does not feel hot a few inches away. However, if you touch it with bare finger, your finger will get a burn due to conduction.

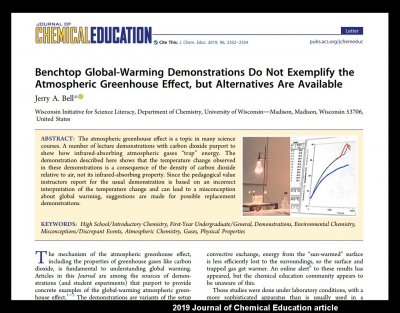

The following sketch shows why adding a sheet on top is analogous to the adding of greenhouse gases or clouds to the atmosphere.

In brief, the baking sheet, like greenhouse gases (including water vapor) and clouds, are very effective at radiating IR. The air in the atmosphere may be warm, yet is not radiating until greenhouse gases or clouds are present. So, on clear, dry nights, we are cooler simply because there is very little above us that radiates IR down.

Capturing Falling Snow in a Cold Fluid

February 15th, 2021Snow is usually imaged in air, the single crystals laying flat on some substrate such as glass. The method is relatively simple, but one must work fast to image the crystal before it appreciably sublimates. Sublimation first rounds out the sharp edges and then causes the crystal to shrink. Generally, this sublimation happens because the photographer is radiating too much heat to the crystal. Conversely, particularly in very cold conditions, the photographer’s breath may deposit fog near the crystal, causing the crystal to grow.

Such issues vanish if one instead captures the snow in a cold fluid before taking the image. To work, this fluid should not dissolve the ice, be less dense than ice, be fluid enough to completely spread over the crystal surface, and be transparent. Other than preserving the crystal, the method has several other advantages. For example, in his laboratory experiments in Hokkaido, Japan, Tsuneya Takahashi lets the crystal fall into a cold suspension of two transparent, cold silicone oils. He sets it up so one fluid is denser than ice, one is lighter than ice, so the crystal falls through the light oil and rests on the (transparent) interface between the two fluids.

This method sounds complicated, so why use it? One, as the oils are immiscible with water, they block water molecules from arriving or leaving the crystal surfaces, so the ice crystal shape is preserved precisely for as long as the fluid is below 32 F (0 C). Two, after imaging the crystal, the fluid is warmed above melting such that the crystal melts into a spherical drop from which he can easily measure the volume and thus infer the mass of the original crystal. A third advantage, more difficult to exploit yet sometimes used, is that he can get top and side views of the same crystal. Other researchers in Japan have also used silicone oils to capture ice crystals in the lab, as well as naturally falling crystals, mainly for the first and third reason. They use just one oil type, a lighter oil. Charles Knight at NCAR in Boulder, Colorado had a fourth reason for using a cold fluid: better imaging. That is, one can image greater depth detail because light scattering off the surfaces is greatly reduced, particularly if the fluid is very clear and has an index of refraction close to that of ice. By reducing the scattering, one can see through surfaces to underlying surfaces. He would use gasoline or hexane fluid.

I don’t have a photomicrography setup to take detailed images of snow, and we rarely get snowfall with nice single crystals anyway, but I wondered how well the method might capture falling snowflakes. That is, could I at least see their rough shapes as they fell through the fluid?

Here, we typically get about one light snowfall per winter (2-3"). A relatively large snowfall happened this past weekend, depositing about seven inches. At first, the particles were small, probably highly rimed single crystals or small aggregates. Later, larger snow particles fell, and these particles were clearly snowflakes (i.e., aggregates). In preparation, the previous night I set out two covered wide-mount jars, one with water, the other with Coleman camping fuel (white gas), which has similar properties to gasoline. In the morning, the one with water had frozen, so I knew the other was also below 32 F.

Outdoors, I set the jar on top of my car, put a wooden chopstick in the jar both to focus on (my camera only has autofocus) and to provide a size reference, set a small LED light panel to the side for brighter illumination, and then opened the lid. The flakes fell into the fluid, and fell down to the bottom of the jar. They fell through the fluid slower than they fell through the air, but it was still too fast for me to see how well they were focused. Turned out that they were not very sharply focused, yet one can still see their general shape and fall orientation (below). In general, the flatter the flake, the more it tends to orient broadside to the fall direction.

Obvious improvements would be a better jar, such as one with a flat, smooth glass front, a better camera, and a thicker fluid to slow down the rate of fall.

Such improvements will have to wait at least until next winter.

--JN

A rare heliac arc? (plus six others)

February 5th, 2019The day starts sunny and bright, but later you note a slight muting of the surrounding landscape. It is still bright enough, but you feel less heat bearing down. Apparently, a thin veil of high clouds has slowly and silently appeared above.

When this happens, please take a few seconds to look up and see what these clouds are up to. Do they have their crystals lined up for one or more arcs, or are they oriented randomly, giving a halo with perhaps a sun dog or two? To the trained eye, the chances are high that such a veil will give rewards, even when no crystals are present. But the crystals give so much more, particularly when they line up in various ways.

Wandering, somewhat exhausted, on the hillside above Index, WA last Monday, I got this very sense of a muted landscape. So, I found a break in the trees, looked up, and instantly felt recharged. A colorful circumzenithal arc had appeared, which by itself is always a treat. But I was also awed by several other arcs and a very diffuse 22-degree halo. Excitedly, I took photos and scrambled around trees and rock for a more complete view.

(As with all images here, click on the image to see a larger view.)

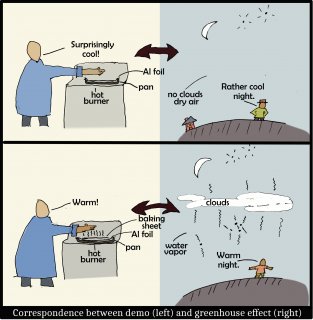

Due to the complex way the eye and brain discerns light and patterns versus the much simpler way of a camera, the patterns are much more distinct when viewed direct by eye. But the above composition has my attempt to compensate the original photo at left, with some contrast enhancement in the middle version, and markings on the right version.

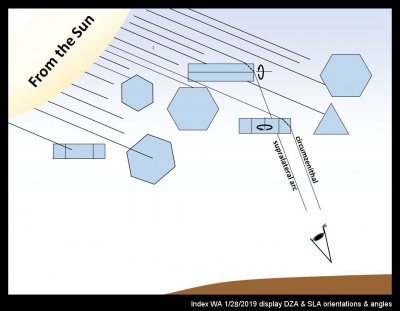

The band of color at the intersection of CZA and SLA is from the oriented prism crystals of the circumzenithal arc (CZA). Their formation is relatively common I think, though a group of observers in Germany apparently finds their occurrence there to be only about 13 times per year (https://www.atoptics.co.uk/halo/whyinfr.htm). What is most remarkable to me is not their colors, but the fact that formation of distinct colors requires that the crystals stay extremely level as they fall (deviations of only a few degrees would wash out the colors). My sketch below shows roughly what is going on here:

(Hold on for a moment, and I'll get to the rare heliac arc below.)

Film frost grains and radiative cooling of the ground

December 10th, 2017December 8th brought the first frost to the Seattle area. This doesn't mean that this is the first time this season that the ground reached 0 degrees C or lower. True, we had gotten snow in late November, though this by itself doesn't mean the ground reached 0 C because snow deposition differs from frost formation. The snow was below zero when it formed in the air, but for the rest of its existence, it could have been melting and the ground itself likely sped up the process by remaining slightly above 0 C. But in contrast with the snow, for frost to form, the ground itself must cool below 0 C.

When I used to put out some metal plates with recording thermocouples, I didn't see visible frost until about -5 C, but that was based on just a handful of measurements. Anyway, what this means is that we may have had a few mornings with some patches of ground (including anything connected to the ground) dipping slightly below zero but with no obvious frost appearing. Also keep in mind that "ground temperatures" reported at weather stations are 1.5-2.0 meters above the ground, and thus may be 5-10 degrees C warmer at night than some ground patches. Why? At night, the ground cools by radiating, and if the atmosphere is not radiating much down, then considerable cooling happens. This is why clear nights are the ones with the most frost or dew.

Anyway, here is one shot of some of this "first frost" on my car window.

The image shows patches of different texture. These regions differ in texture because they are tiny hoar-frost (i.e., vapor-grown) crystals of differing size or orientation. That is, they stick up differently in different patches. They stick up differently because they sprouted off of a thin layer of film-frost that had a different crystal orientation. So, the patchy look comes from the different grains in the film-frost. See some of my previous posts with diagrams about this phenomena (category: "film frost"). Here is one with particularly helpful diagrams.

http://www.storyofsnow.com/blog1.php/choppy-waves

-- JN

A Fogbow

October 25th, 2017A fogbow, or cloudbow (fog is a type of cloud), is a special type of rainbow. It is just white, and so not as often photographed as the full-spectrum rainbow, but it can be exciting to see nevertheless.

The reason the fogbow is white is because the water droplets in fog are much smaller than raindrops. Fog droplets may vary in diameter roughly between 1 and 20 millionths of a meter (i.e., 1-20 microns), whereas raindrops are typically 1-3 thousandths of a meter, or about 500 times larger. The wavelength of visible light is only about a half a micron, so the light rays inside a fog droplet are still fairly well defined, but there is simply not enough room to separate out the colors, to state things simply.

Upon approaching a fog in the morning, look towards, but above your shadow. About 50-60 degrees from the shadow of your head is where the fogbow will sit, just as it would for a rainbow. Evenings will work too. But midday, the angles 50-60 degrees above your shadow will have you looking at the ground, so you probably won't see a fogbow there. (If you are in an outdoor shower, you might see a rainbow though.)

The above photograph shows the fogbow I saw yesterday morning, about 8:30 am, biking into a nearby park.

-- JN

How clouds form snow

January 14th, 2017To understand snow formation, one must know a little about clouds.

Q: What is in a cloud?

A: Air, dust, vapor, droplets, and often, ice.

Q: How much air? How much liquid water? How much ice?

A: The answers will probably surprise you. See my short 20-min presentation below. I gave this recently to the Bellingham, WA Snow School. (23 slides, but due to file-upload-size restrictions, I had to put them into three parts below, 10 slides, 6 slides, 7 slides.)

Snow, rain, and weather affect everybody, yet how many of us learned in school even the most basic facts about precipitation in school?

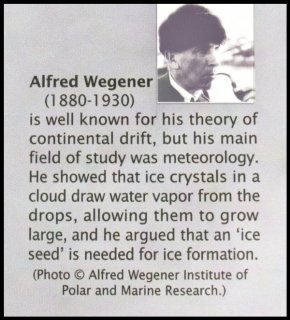

Q: Who first realized how ice grew in a cloud?

As described in my presentation, he realized this by observing frost on the ground.

Q: Who first realized how Alfred's theory was intimately connected with rainfall?

Tor discovered this by observing fog in a mountain forest, and like Alfred, applied some of his physics knowledge.

In my presentation, I discussed Alfred Wegener, the roles of the different cloud components, and briefly how the ice, once formed, takes on its strange shapes:

First 10 slides (with blue text added to account for the things I said during the talk):

http://www.storyofsnow.com/media/blogs/a/Jan2017/snowschool_annotated1t10.pdf?mtime=1484585328

Next 6 slides:

http://www.storyofsnow.com/media/blogs/a/Jan2017/snowschool_annotated11t16.pdf?mtime=1484585328

Last 7 slides:

http://www.storyofsnow.com/media/blogs/a/Jan2017/snowschool_annotated17t23.pdf?mtime=1484585309

Later, I will show specifically how the ice gets arranged into all these strange shapes.

- JN

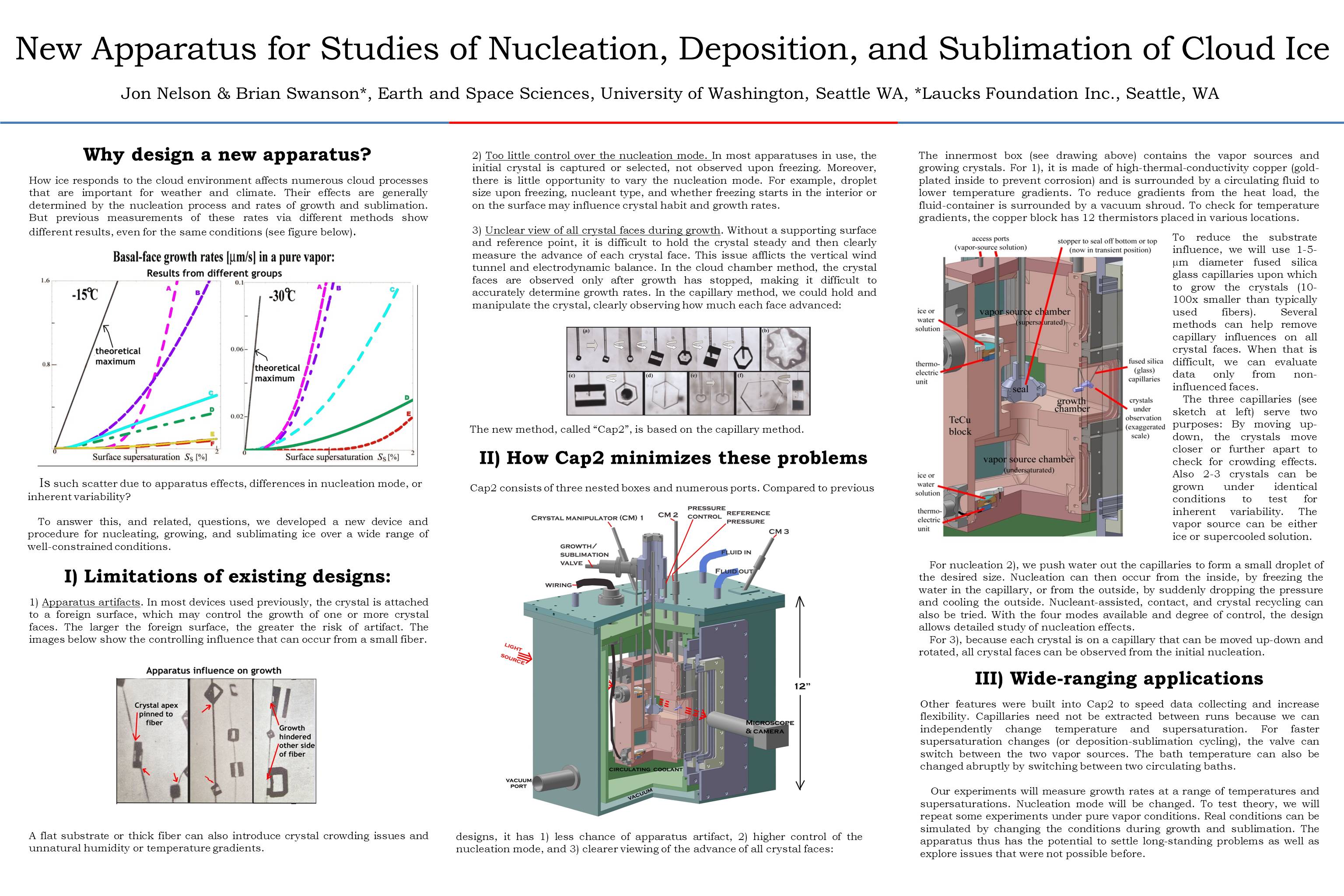

The new ice-crystal-growth apparatus

July 1st, 2014After a few years in the making, our new device for growing single ice crystals in a well-controlled laboratory environment is nearly ready. We are just adding a few small accessory pieces to allow us to start testing. I was to describe the apparatus at the cloud-physics conference this month in Boston, and made a poster to present, but decided to opt out. But, having spent a few days making the poster, I present it below.

As with all images here, click on image to see large-scale view.

And below is the same, but in blog format.

Halo in the sky? Uh, I don't see no halo...

April 20th, 2014After a few days of fine bright spring weather, the barometer falls and a south wind begins to blow. High clouds, fragile and feathery, rise out of the west, the sky gradually becomes milky white, made opalescent by veils of cirro-stratus. The sun seems to shine through ground glass, its outline no longer sharp, but merging into its surroundings. There is a peculiar, uncertain light over the landscape; I 'feel' that there must be a halo round the sun!

And as a rule, I am right.

The quote, from Minneart* describes a common ice-related atmospheric apparition. It appears in skies all over the world far more often than the rainbow, yet few notice it. As a graduate student, I read about halos and often looked for one, but didn't notice it myself until someone else pointed it out. As a post-doc in Boulder, I was out walking with Charles Knight, and I mentioned my lack of success. He glanced up near the sun, pointed, and said “why there's one right now”.

What I had missed in my readings had been the fact that most halos are rather indistinct and often incomplete circles. Indeed, now when I point out the most common one (the 22-degree halo) to someone nearby, they often don't see it. But occasionally, it is sharp enough (and colored) to the extent that anyone will see it if they bother to look up and glance toward the sun. And often it occurs with other ice-crystal apparitions that are even more obvious.

Last fall, while perched high on a rock face, belaying my partner up**, I saw such a vivid display.

The bright spot is called a “sun dog”, “mock sun”, or “parhelia”. They, one on either side of the sun, usually appear together with the 22 degree halo. Indeed, the sun dogs very nearly mark the spots where that halo intersects another arc called the parahelic circle. Their cause: horizontally oriented, tabular ice crystals.

The end of snow

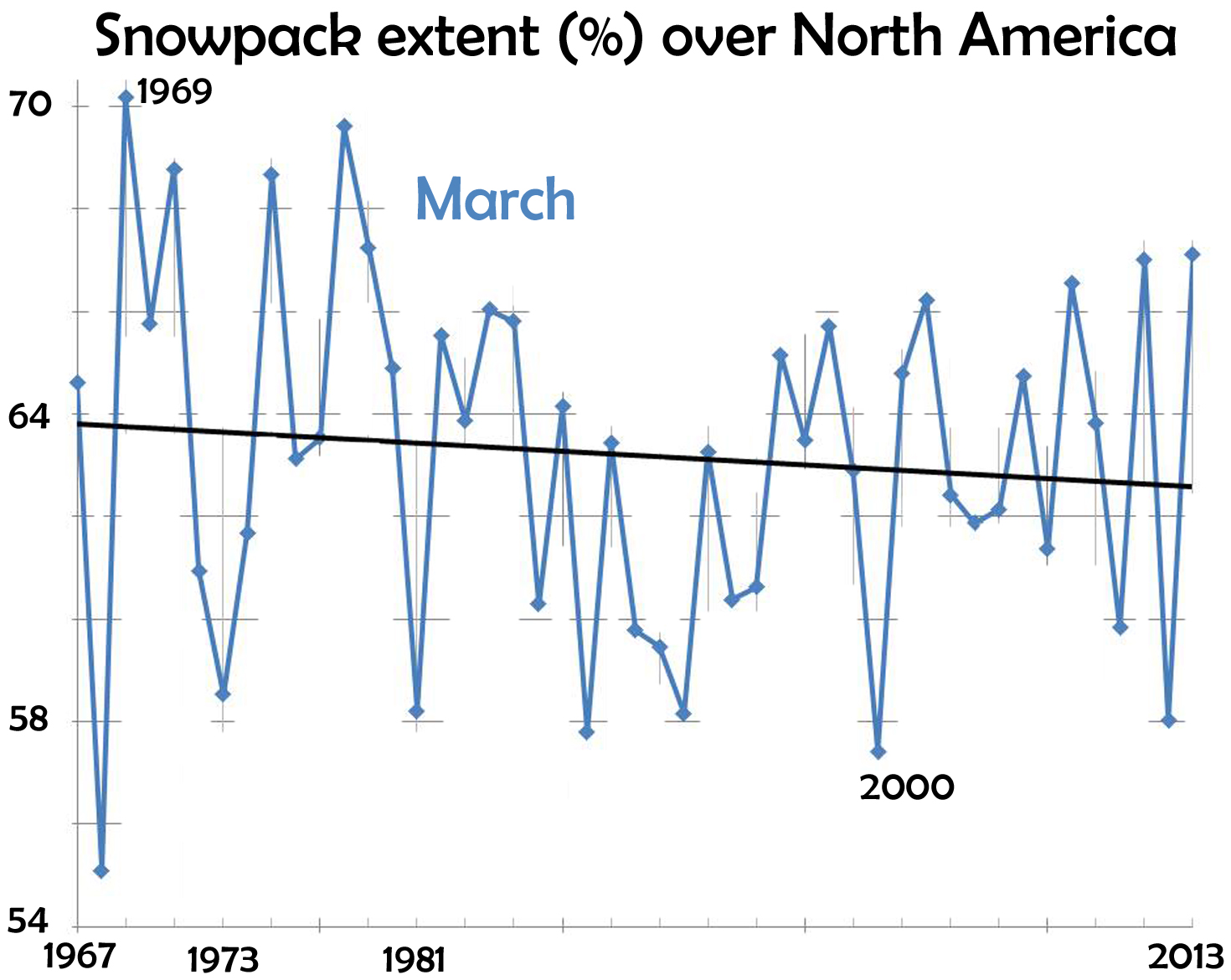

March 1st, 2014This recent front-page article caught my eye:

The writer is an avid skier-snowboarder, and thus concerned about the future of his sport. The facts he relates paints a grim picture:

- In the past 47 years, a million square miles of spring snowcover has disappeared from the Northern Hemisphere.

- Since 1970, the winter warming-rate has been triple the rate of the previous 75 years.

- The Alps are warming 2-3 times faster than the world-wide average.

- Potential Winter Olympic venues shrinks from 19 (now) to 6 by 2100.

and many other facts. Avid skiers like spring skiing. For March, the data (from Rutgers University Global Snow Lab) show a decline in area covered by snow.

Rime, freezing fog, and crystalline spider webs

January 22nd, 2013The Pacific Northwest has been foggy a lot lately, but the fog droplets have been subzero, or supercooled. When such fog droplets hit an object, they almost always freeze. The resulting frozen aggregate is called rime. Freezing fogs make rime.

The resulting rime formations may look like hoar frost, or even snow, from a distance. But close up the special features of rime become apparent.