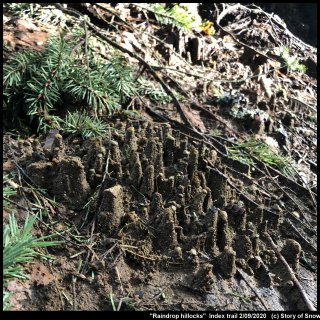

Raindrop Hillocks and Ground Ice

February 16th, 2020Ever see these small centimeter-scale hillocks in dirt or sand, usually topped by a small pebble or twig? To me, they look like a miniature mountain landscape. A brief reflection on their appearance suggests erosion by raindrops: The drops fall down on and near the larger grain (e.g., pebble), pushing the smaller grains down, leaving the larger ones to stick up above. In this way, a scene of tiny hillocks emerge. I call them "raindrop hillocks".

Click on any image to enlarge it.

Soft, easily compactable soil seems necessary to their formation. Just toss some loose dirt into a pile, then come back after a heavy rain and you are likely to see something similar. But further reflection may present some difficulties. For example, some hillocks occur where the soil should not be loose. The above image presents one such case: here the soil was on a well used trail where the soil had long been compacted. Clearly such soil could not be so easily carved by tiny raindrops. The case pictured below is on a level sandbar after a river shifted course. Where did the sand go that was up near the peaks? It seems that the sand must have originally been very loose. How could this be?

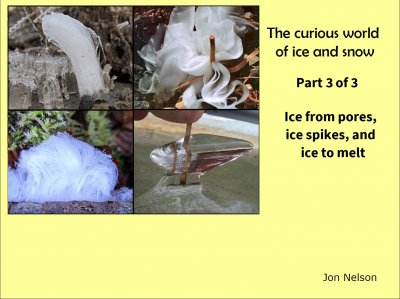

The Curious World of Ice and Snow: Part 3 of 3

February 8th, 2020These 14 slides are the final (third) section of my Science Cafe talk. (Plus two slides added as an introduction.) As in the previous section (previous post), this section mostly has ice forms that come from the melt, but the ice shapes here are a little "hairier". And at the end we return to forms influenced by the vapor. As with all these forms, I doubt any could have been predicted before their discovery. Nature is complicated, so Nature surprises us.

Click on any image to enlarge it.

As before, the green font below shows the content of this section. The first five cases involve melt flow along surfaces and in narrow pores. Remember that melt is another name for liquid. (The term melt is more accurate though, as it implies pure water, whereas liquid could be water mixed with any solute. For example, salt water is a liquid, but it is not melt.) As mentioned in part 2, their formation from the melt means that they tend to grow relatively fast and large.

First up is perhaps the most common. Do you know what is going on when the ground becomes crunchy?

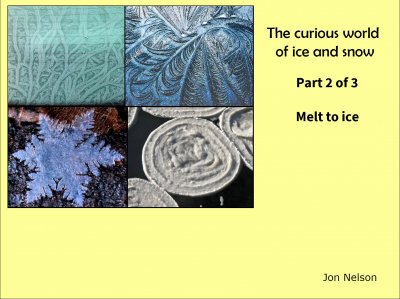

The Curious World of Ice and Snow: Part 2 of 3

February 8th, 2020As I mention in Part 1, these are slides I gave for a Science Cafe discussion session in 2012. This section focuses on ice that forms directly from the melt, that is, the liquid phase. Contrast these cases with those in part 1 in which the ice grew from the vapor. Some of these cases might seem a little familiar, but many ought to seem downright bizarre.

As always, click on an image to enlarge it.

The contents here are emphasized in green font below. The underlying difference between ice growth from vapor and from melt is that the melt is much denser. The higher density means that vastly more water molecules can impinge on the ice surface in a given time and area. This higher impingement usually means faster growth and larger crystals, but the way that the melt reaches the crystal influences the form, and the result is not always so obvious. In fact, I would even say that it is never obvious.

OK then, let's get right back into it.

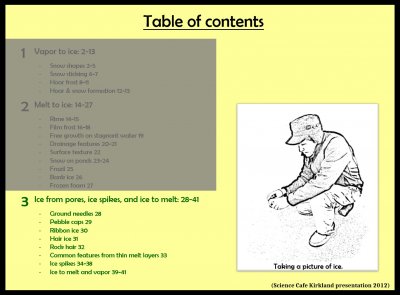

The Curious World of Ice and Snow: Part 1 of 3

February 4th, 2020In 2012, I gave a "science cafe" talk with a local series sponsored by the Pacific Science Center, KCTS public television, and Science on Tap. The title was "The curious world of ice and snow". The location was a bar in Kirkland, but open to all ages. When I showed up with my family, they tried to seat us in the backup room, the regular room having filled up, but I said "Oh, well I'm the speaker" and they kindly created a space for my family in the regular room. I was indeed surprised at the crowd. People are apparently more interested in ice than I thought. (Hmm, but where are they when I post here?)

Click on any image to see an enlargement.

The basic structure of each talk was to give a lecture of about 30 minutes and then allow up to an hour (I think) for the Q&A. In my excitement, I had created 41 slides, in retrospect too many for the allotted time.

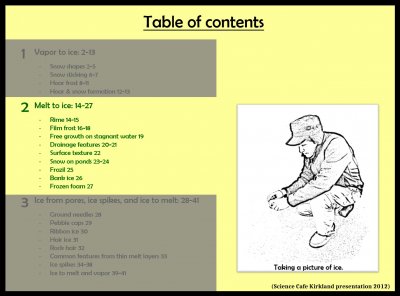

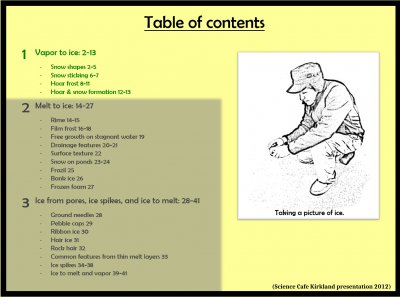

Given all the time spent preparing the slides, I hope that by posting them here that even more folks can enjoy the images and discussions. But, instead of unloading all of them on you at once, I will break the discussion into three sections. By adding the following table of contents, each section will have 14 new slides and the total will be 42, which according to Douglas Adams* is a really special number.

The contents of this section is part "1", written in green font.

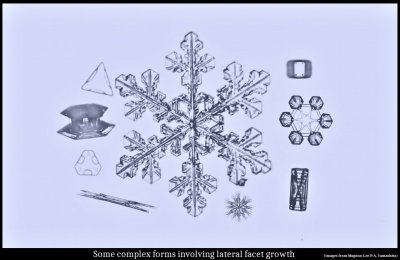

Some "Inexplicable" Snow-crystal Features: Applications of Lateral Growth

January 29th, 2020Last October, I gave a talk at the University of Washington about our recent experiments and ideas about snow-crystal growth. My pitch was general and short, as few folks work in this area and I'd hate to bore them with a long lecture. So, I was delighted to see quite a few graduate students in the audience, some of them asking good questions.

Instead of giving the narrated presentation here as a video, I will give the slides (23) with brief explanations similar to what was spoken at the talk. Narration below each slide. Skip to the ones that look interesting, and click on them to enlarge.

The Growing Icicle's Hollow Tip

January 17th, 2020If you inspect the tip of a growing icicle, you might be surprised to find it hollow. Skeptical? Well, if you think the conditions suitable for icicles outside, put a toothpick in your pocket and go outside. Then when you see a likely candidate, poke its tip with the toothpick.

Click on the image to enlarge.

Not all icicles are growing, of course. If the supply of flowing water has dried up, the tip may be solid, or if the air has gotten warm, then the tip may be rounded and wet. The pic below shows a longer, but solid-tipped, icicle next to the growing one. Its melt-water source is too low for the tip to grow.

Transitional situations occur as well, such as the icicle that just started to melt and still has a hollow tip, or the completely solid icicle that just starts growing again and has yet to develop a discernable hollow. The drip may also be intermittent. You might not find that growing icicle right away, but keep that toothpick handy.

As to why a growing tip is hollow, I won't attempt to prove it here, just try to make it seem plausible. Spend a few moments considering the following two simpler situations that show the basic ideas. You can even apply these ideas to other forms involving freezing water...

Martini Hoar (raise a tiny glass?)

October 19th, 2019The hoar-frost crystal shoots up like a thin, solid straw, then suddenly opens up into a cup-like shape. I have seen it often enough to give it a name: "martini hoar".

The cup can be weirdly segmented and polyhedral, but it nevertheless widens suddenly. Here are a few more (Sorry for poor photos—someday, I hope, I'll get better about photography.)

Here is a larger view of the region. Note the similar hoar coming down from the top, but without a clear view of the base.

This sudden widening feature has bothered me for awhile, but I was delighted the other day to figure out a plausible reason. My delight was made even greater because the reason involved measurements I made in the lab two decades back. The measurements were to understand snow-crystal habit, but apply equally well to hoar frost because hoar grows just like snow except it is attached to the ground.

Now that I have viewed some of the older pictures I took, the actual growth phenomenon looks more complicated in terms of crystal shape, so I am not so sure my reasoning explains things so simply. Nevertheless, it should apply well to many cases, and at least is worth learning because it involves important growth principles that also apply to snow.

Drainage Lines on Snow

October 18th, 2019Last night I dreamed of a passage along a narrow river in a thick forest followed by a perilous descent down steep snow on a mountain.

And then this morning a friend sent me this picture.

Actually, I had asked him about the photo yesterday, so that explains my receiving it. I had asked because the lines in the picture had originally puzzled me. They appeared to be flow-lines, but this is a snowfield, not a glacier, and even if it was a glacier, the cause of the darkening wasn't obvious. But after talking about them with Steve Warren at the UW on Monday, I came to a simple conclusion. They are indeed flowlines of a sort, but it is not the ice that flowed. Rather, it is liquid water. That is, they are channels created by rainwater drainage.

Still, it doesn't detract from their beauty, does it?

And, in a weird way, it connects to my dream... as if my mind had assumed the form of a raindrop and fallen onto the snow.

--JN

Thinking Laterally in Crystal Growth…and in Science Publishing

October 10th, 2019After a long period of work (on and off), we have an accepted paper on the corner pockets we discovered (see here). But during the writing stage, I thought about collecting earlier ideas I had developed during my correspondence with Prof. Akira Yamashita in Japan, and as a result, the paper ballooned. Originally, it was to be a short note about the pockets, but in the end, the central theme was instead the new notion of the lateral (or sideways) growth of crystal facets. Actually, one type of lateral growth had been long known, sometimes called "facet spreading", but we collected together three types of lateral growth and describe how two of them are particularly useful for explaining a wide range of observed features on snow and ice crystals.

But before describing some of our findings, recall that all science publishing costs money. Almost always the research grant pays the page charges. However, our grant ran out three years ago, and this paper is particularly expensive (estimate: $3600) because we needed many pages to argue our points and show how lateral growth can explain many growth forms. If you can contribute, we will gladly send a signed copy of the paper acknowledging your help. Or, if you have just enjoyed some of the articles on this blog and would like to help me continue, you can contribute here as well. Here is the link:

https://www.gofundme.com/f/publish-a-research-paper-on-snowcrystal-formation

The paper in its submission format is 58 pages: (as always click on the image to enlarge)

The published format will reduce the length a little (mainly shrinking the figures), but it will still be much longer than the standard 10-15 page paper.

One key figure to help explain some of these "lateral" concepts appear in Fig. 2, reproduced below. This figure shows a just-frozen droplet, which is often called a "droxtal". Crystal facets have appeared for eight faces, shown as the shaded flat regions in the top sketches.

Dark lines in melting snowpiles

March 30th, 2019Snow cleared from a city street slowly vanishes, leaving lines of "dirt".

(Click on images to view more closely.) Where the snow has a distinct edge, you can see the dark lines are ridges, some of which can be quite sharp:

Why is this?

Cryoconite ridging

This all happens because the snow is vanishing but the dirt is not. The vanishing is actually called "ablation", meaning some combination of melting, sublimating, and evaporating. It is mostly melting in the above case, but it is possible that evaporation helps to form the lines. About the dirt, it is not clear exactly what it is. The term "cryoconite" is used when similar dark dirt falls and clusters on glaciers and ice sheets, so to be specific, we might call it "cryoconite ridging".